This blog is written by Community Engagement Officer, Sally Hyslop who coordinates DCRT’s Riverfly Monitoring Initiative volunteers.

Citizen scientists across the UK help to monitor pollution in our rivers in diverse and exciting ways. Some volunteers check water quality, testing for chemical signs such as increased pH or high phosphates, nitrates or ammonia. Others wade up and down rivers looking for the smells and sights of sewage pollution, checking if sewage outfalls are discharging incorrectly and hunting out misconnected drains. Scientists also utilise another method which involves surveying the species living in freshwater, some of which are useful ‘indicator species’. Monitoring changes in these creatures’ abundance can provide evidence for decreased water quality and potential pollution events.

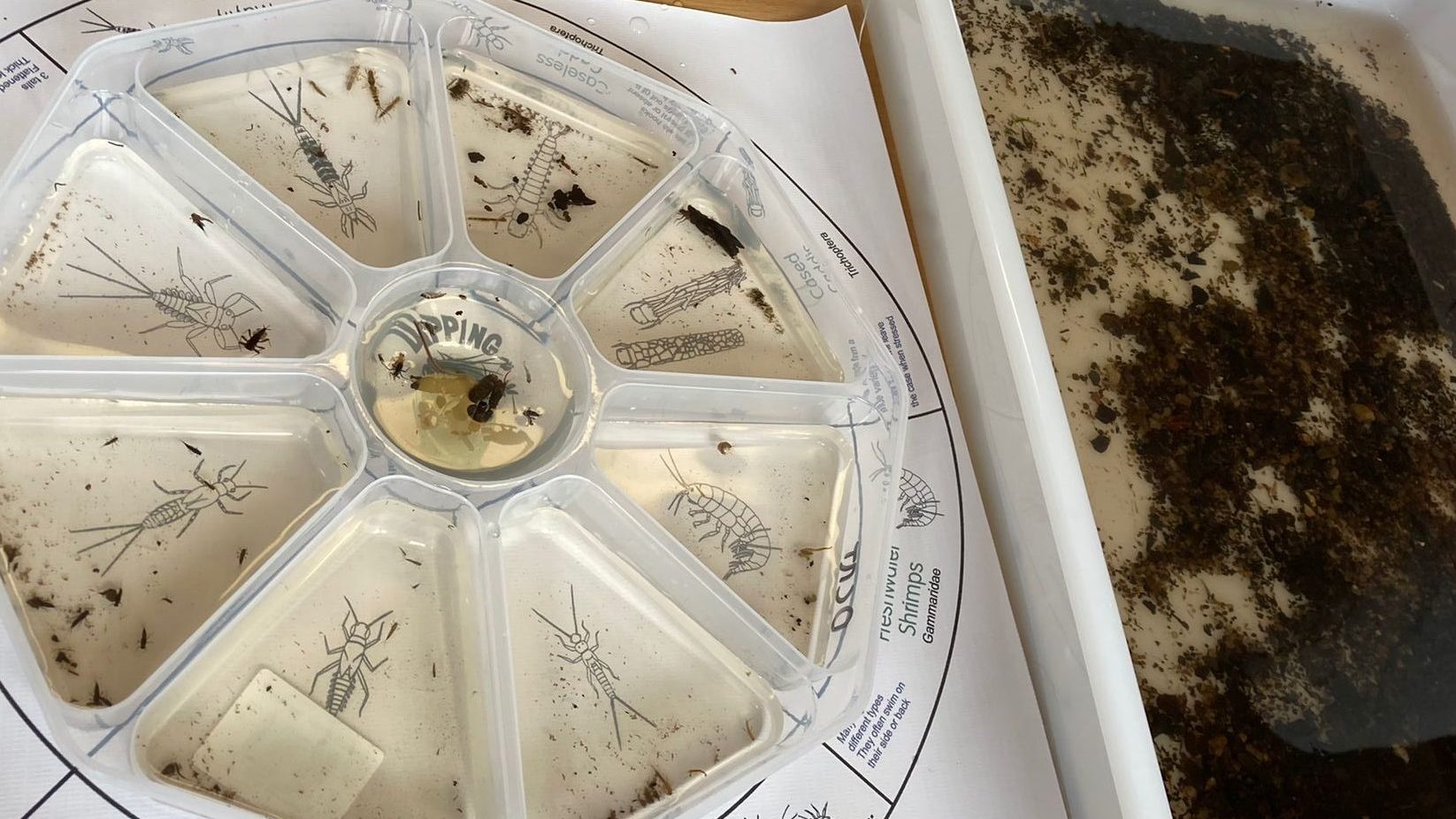

The Riverfly Monitoring Initiative, known as ARMI, is a nationwide project from the Riverfly Partnership, whereby volunteers sample and survey a small section of their local river each month. Surveyors are trained to ‘kick-sample’ the river, disturbing the bottom of the riverbed with their feet to dislodge freshwater invertebrates from the sediment and into their nets. This methodical approach allows volunteers to discover how the community of freshwater invertebrates, also known as riverflies, in their local stream changes throughout the year.

Volunteers are trained to identify 8 different types of freshwater invertebrate, which are often the larval stage of flying insects. These include nymphs from 4 different families of mayfly, cased and case-less caddisfly larvae, stonefly larvae and freshwater shrimp. Volunteers may find many other different types of freshwater invertebrates, such as leeches, midge larvae, snails and aquatic worms, – but it is the 8 designated groups that they are specifically looking for. These groups have been chosen for their relative abundance throughout the year, their presence in different rivers and habitats across the UK and, perhaps most importantly, their sensitivity to severe pollution events. These riverflies struggle to thrive in the low diffused oxygen conditions, the high concentrations of heavy-metals or the thick sediment assosicated with pollution events.

By counting up the representatives of each group, volunteers collect and build-up data on how their site changes each month, allowing them to spot long-term trends and possible problems. When there is a sudden drop in the abundance of invertebrates, the data may indicate a potential pollution incident. At this point, volunteer groups can alert the statutory body and present the evidence they have collected. This leads to an investigation of the site for pollution. By working together at different sites along the same stretch of river, volunteers can also check how far pollution may have spread, where along the river it may have started and how quickly the river takes to recover.

Through the Riverfly Partnership citizen science scheme, volunteers across the country have created a networked alarm system for the health and condition of our streams.

DCRT deliver training for groups wishing to start a Riverfly Monitoring Initiative scheme and coordinate 3 different groups across the Don Catchment – you can find out more about training here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.